Burt Bongart was throwing away his three television sets when he got a call from Rabbi Gershon Grossbaum of Upper Midwest Merkos-Lubavitch House in St. Paul, Minn.

“We need your house so the community can come and watch the Rebbe on cable,” said Grossbaum, referring to the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. It was 1981, and the Rebbe’s weekday Chassidic gatherings, called farbrengens, were now being beamed through cable TV. It was the dawn of the satellite era, yet most members of the Chabad community in Minnesota did not own TV sets, let alone have cable or satellite service.

“Gershon, I’m throwing them out,” Bongart replied. The Bongarts had become more religious over time and with young children around, they did not want the pop-culture values dominating the airwaves filling their home.

“Well, don’t do that,” was the reply.

So Bongart didn’t, and over the next few years, remaining faithful to his intention of increasing the sanctity of his home, the TV set in the family’s spacious St. Louis Park home became the Jewish community’s “go to” address for watching the farbrengens, drawing participants who would drive from as far as Iowa just to see them.

Those who have ever attended one of the Rebbe’s farbrengens are quick to describe the energy they felt in the room. From his base at Lubavitch World Headquarters in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., the Rebbe would speak for hours on a wide array of Jewish and societal topics, the scholarly talks interspersed with song and blessings of l’chaim, “to life.” Listening to the live event via telephone hookup had been done for at least a decade, but television was the new frontier. Through satellite, the Rebbe could now be seen by people around the country, who were aided by the simultaneous translation done by a young Minnesota-based rabbi, Manis Friedman.

Bongart felt that every farbrengen was momentous, so he recorded them. Nothing fancy—just on a regular VHS tape. He could never have imagined that 33 years later, one of those recordings would be the key to reconstructing the full video of the Rebbe’s farbrengen of July 14, 1981.

Now, after much painstaking work to restore the aging cassettes, the full video will be released for the first time ever by Jewish Educational Media (JEM) in time for the Rebbe’s 21st yahrtzeit—the anniversary of his passing—which begins on the night of June 19.

The Missing Tape

It was for the work of broadcasting the Rebbe’s farbrengens that Rabbi Hillel Dovid Krinsky founded JEM in 1980. Chabad had long recognized the power of modern technology to reach wider audiences, and it was the Rebbe himself who had encouraged the late Rabbi Yosef Wineberg to begin teaching the Chassidic work of Tanya over the radio in 1960. With the combination of satellite technology and public access to cable television, beaming the Rebbe’s farbrengens around the country became possible—and an opportunity the Chabad-Lubavitch movement embraced.

From the packed basement synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights, the Rebbe’s gatherings became worldwide occasions, and a new sphere of people—Jews and non-Jews from all walks of life—were suddenly exposed to the Rebbe’s universal teachings.

Since the Rebbe’s passing in 1994, JEM has focused on restoring, archiving and publishing multimedia relating to the Rebbe, Chabad and Judaism at large, and among its collection of materials are hours of footage of the Rebbe’s farbrengens. The collection is vast, but JEM has worked hard to restore the recordings and regularly publishes videos of his talks, advice and archival scenes, which have been restored, color-corrected and subtitled in six languages.

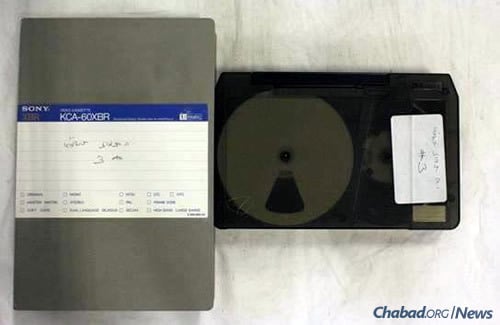

Earlier this year, during a regular inventory of its state-of-the-art archiving site—the footage JEM owns was filmed on a wide array of recording mediums and restoring the degrading recordings has been a years-long, not to mention costly, process—a box filled with old U-matic videocassettes was discovered.

“Our archivists were looking through these boxes, and they found undocumented tapes of this 1981 farbrengen,” explains Rabbi Elkanah Shmotkin, JEM’s director. “We knew JEM had broadcasted the event, but these particular recordings went missing shortly after the original broadcast, and we just couldn’t locate them until now.”

With the newly found box in hand, JEM worked with a group of preservation experts to painstakingly restore the tapes, hoping to release this heretofore unseen farbrengen. The archivists were excited until they discovered that one full tape remained gone, having most likely fallen through the cracks years earlier.

“There was no way we could release the video with the end of the Rebbe’s second talk and the lion’s share of the third talk missing,” says Shmotkin. “Our team knew we just had to find it and release the entire event.”

‘Moment of Silence’

The 1981 farbrengen in question took place on the anniversary of the release of the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—from a Soviet prison in 1927. During the four-hour-long event, the Rebbe discussed youth violence, which he sourced to the breakdown of values at home and lack of acknowledgment of a Higher Power in schools. The talk took place shortly after multiple cities in the United Kingdom had been rocked by race riots, with the Rebbe pointing out that rates of violence at schools in New York and elsewhere had been rising for decades.

“Generations of children—boys and girls from diverse backgrounds and nationalities—are being sacrificed to this ‘idol’ that a child dare not be taught or reminded that there is a Higher Being above him,” said the Rebbe. “That there is ‘an Eye that sees, and an Ear that hears,’ and all one’s deeds carry consequences.”

Advocating for a “Moment of Silence” in public schools was a recurring theme of the Rebbe’s. As he did on other occasions, he explained that rioting and violence stemmed from the unusual zeal with which the principle of separation of church and state had been enforced in the American educational system. It was especially shocking considering the faith in an Almighty G‑d upon which America’s founding fathers had so deliberately placed at the center of their great experiment.

A Growing Interest and Audience

“Interest in the Rebbe’s farbrengens continues to grow, even 21 years after his passing,” says Shmotkin, who over the last two decades has overseen JEM’s growth from a repository of videos to a high-tech multimedia operation. “This specific talk is the only broadcast that we were missing since the televised farbrengens began, and it was especially providential that it turned up now. We knew we needed to publish this recording.”

Dr. Michael Maling, a Chicago-based philanthropist who co-sponsored the project, says that the timing could not have been better: “Our society is thirsty for direction and meaning. The Rebbe’s words on the vital importance of moral education are so timely, they could have been spoken today.”

Sponsoring the farbrengen release, Maling says, is his way of helping perpetuate the Rebbe’s message. The release is also co-sponsored in memory of Rabbi Nachman Sudak, chief Chabad-Lubavitch emissary in the United Kingdom for 55 years, who passed away last summer.

At the time, the Rebbe spoke with a sense of urgency, emphasizing that if the issue was not remedied speedily the situation would continue to deteriorate. The Rebbe spoke in Yiddish: “The first solution is not to wait until the child becomes a danger and then throw him into jail, where he costs the taxpayer vast sums of money ...

“First and foremost, don’t destroy the child. Don’t raise children to be thieves and robbers! Teach the children that there’s ‘an Eye that sees and an Ear that hears!’ ”

An Attic in Brooklyn

With four-and-a-half months left until the hoped-for publication date, the staff at JEM got to work trying to track down the missing tape. Inquiries were placed to sources from California to Israel, but the tape could not be found. It was then that someone thought of calling Bongart, who has lived in Brooklyn since 1988.

“We called Mr. Bongart before Passover, and he searched through his entire collection of recorded tapes of the Rebbe, but he couldn’t find that particular date,” says Rabbi Motti Groner of JEM. “It looked like we were at a dead end again.”

To make matters even dimmer, Bongart owns a media transferal company called Total Digital Now, and had begun digitizing his collections of VHS tapes a few years earlier, which meant he knew his inventory pretty well. Determined, the team at JEM decided to try again.

Bongart suggested searching through another stash of boxes, thinking that it might have somehow gotten mixed into the pile. With help from his son Yisroel, down from the attic came the aged cardboard boxes, some 400 tapes in all.

“I know it sounds clichéd,” says Bongart, “but when we reached the tape at the very bottom of the very last box, we popped it in and Elkanah exclaimed, ‘I think this could be it!’ ”

It was.

“He told me that to JEM’s knowledge, it’s the only one in existence,” he adds proudly.

In the months since, JEM has put hundreds of hours into restoring, producing and translating the full video of the farbrengen. Efforts to make the Rebbe’s talks available for the public is at the core of JEM’s work, and tracking down this particular farbrengen, notes Shmotkin, is particularly satisfying.

“It’s rewarding to discover a hidden time capsule, and to see how relevant and fresh the Rebbe’s message still is,” he says. “We also recognize the excitement with which it is being received and the impact it will surely have.”

As for Bongart, he’s humbled just to be a part of it.

“The Rebbe has done so much for my family,” he affirms. “I’m so happy that I could do something to preserve his teachings so others will be able to continue benefiting from them, too.”

Join the Discussion