It was only last Monday that I took the bus to Beit Meir, the graceful little mountain-top village 20 kilometers west of Jerusalem, in order to visit Yoram Raanan. Yoram is a new friend, though the kind you feel you have known and cherished for years. When I first chanced upon a print by the artist a number of years ago—it was his masterpiece, “Mount Sinai”—it took my breath away, quite literally. And when I saw his work featured on Chabad.org, I grabbed the first opportunity to meet him in person.

Yoram and I paced up and down his lush studio, which was overgrown with exquisite paintings of biblical scenes and waterscapes and phosphorescent menorahs and glowing human souls—a veritable small Garden of Eden burgeoning with canvases, paint, and the uncanny ambience of something holy going on.

I remember our first meeting a few months ago. “I have no intention of flattering you,” I announced, just after shaking hands. “Good!” he snapped back instinctively, unafraid of insult.

“I will not flatter you,” I said, “because I sincerely believe that your work is nothing less than an event in the history of painting.”

He accepted my words with a smile free of both vanity and false modesty. And I, for my part, followed through by writing a long article, a kind of exercise in “art criticism,” in which I have attempted to articulate why the oeuvre of Yoram Raanan marks an event in art history, certainly in the history of Jewish art, if not beyond.

Then the Fires Came . . .

In the middle of the night last Thursday, on the 24th of Cheshvan, the village of Beit Meir fell victim to fires suspected to have been started by Palestinian arsonists. Yoram’s studio was entirely burnt down.

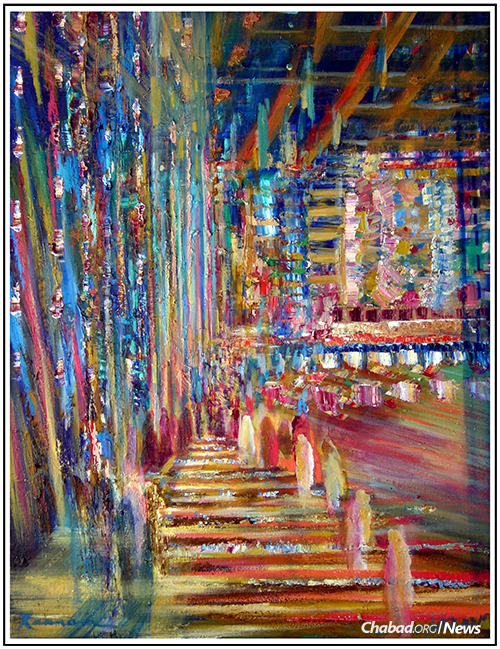

When I heard the next morning what had happened from the artist’s wife, Meira Raanan, the news knocked the wind out of me. All those masterpieces! The luminescent “Shir HaMaalot,” which took one into the Beit HaMikdash! The awesome convulsion of the Sea of Reeds in “Beshalach” (behind Yoram in the photo below)! The haunting emerald “Esther” that had once been a painting of an eagle hanging in the Sheraton Plaza! The blazing menorah of “Vayakhel” in which gold of the candelabra had been alchemically transformed into pigmented fire!

The loss of so much beauty—all of it dedicated to G‑d, all of it reflecting subjects from Jewish life and Jewish history—constitutes an inestimable loss for Jewish culture. It goes without saying that Yoram has sold many paintings over the years. But there were certain landmark pieces, including all but one of the pieces I mention in my article that still patiently awaited appreciative buyers. Besides the hundreds of paintings stacked against the walls of the studio, there were hundreds upon hundreds of sketches and half-finished works stuffed in drawers, which had slowly accumulated over four decades of prolific labors.

The prospect of speaking to Yoram himself after this cataclysmic loss, I must confess, made me quite nervous. Finding adequate words to comfort someone who has lost an enormous amount of personal property is difficult enough. Lost property is labor lost. But how do you comfort an artist who has lost an enormous amount of expressions of his very heart and soul? How is one consoled for the loss of deeply personal, spiritual labor? Before we had a chance to speak, we exchanged a few furtive emails before Shabbat.

‘This, Too, Is for the Good’

Yoram wrote: “Studio total total loss.”

I wrote back: “Can you talk? I can’t imagine what you are going through.”

Yoram: “I know you can understand and appreciate your concern. House and kids OK. Everything in and of my studio and surrounding area are completely finished. Gam zu l’tova. Shabbat shalom.”

Gam zu l’tova. “This, too, is for the good.” The phrase is a wonderful profession of faith in the face of despair. But to my mind, a hundredfold more astonishing and more wonderful is the expression, jotted under such dark circumstances: “Shabbat shalom.”

After Shabbat, I have a chance to talk to Yoram face to face. He explains his feelings with the same characteristic simplicity: “With emunah, there are no half-measures. You either trust Hashem or you don’t.” He describes to me how, during the frantic evacuation of Beit Meir, he looked back toward the trees under which his studio lay and saw the conflagration rise into the black sky. “I resigned myself there and then,” he said. “Everything is in the hands of G‑d. G‑d knows what He’s doing. You know, it made me think of a korban [‘offering’].”

“Like an olah [burnt offering]?” I ask, immediately regretting my two cents.

“Yup,” he says, with an almost melancholy smile. And he jokes about how often fire appears in his paintings—the flames of the menorah, the fire on the altar in the Temple, the fire of Torah.

Then, without batting an eyelash, Yoram immediately goes on to elaborate on how much good has already come of the destruction. “I can’t believe how many emails I’ve received! So many people are writing and calling and want to help out! People are coming to my website and discovering my art for the first time! It’s amazing!” His eyes are full of wonder and gratitude as he enumerates the acts of kindness and appreciation streaming in from all corners. He insists on seeing the destruction as an opportunity.

We talk about the various mundane issues that will now require his attention in the next months: the damage assessment, the police investigation, the plans to rebuild the studio (“It’ll be better than the last one, taller! More mental space to think higher! To paint bigger!”), the need to publish a book of his paintings and the prospects of finding a patron to fund the book.

“What about getting back to painting?” I ask.

“Yes!” his eyes light up and his mind begins to race, “Absolutely! As soon as I have a space to lay down some canvasses and start pouring out the paint! Let the phoenix rise from the ashes!” Yoram evidently intends to fight fire with fire—the profane fire of destruction with the holy fire in the Jewish soul.

I doubt many readers have the patience to plod through my “highbrow” analysis of Yoram’s work. I wish there were some simple way for me to communicate why supporting his work is, from the standpoint of Jewish culture, less like a luxury and more like a necessity. A number of very welcome initiatives have been set up to raise money to rebuild the studio.

Yoram himself muses: “Better than sending money, why not buy a print? It’s a ‘win-win’ that way.”

As a very biased fan of Yoram’s work and someone concerned with spreading the hallowed beauty of his art—no less than with seeing him resume his labors of love—I cordially invite the reader to check out his website: www.yoramraanan.com. And to keep an eye out for more to come from Beit Meir.

Join the Discussion